Writing Rebel

by Chale Naufus

Stewart Stern lay in the darkened end of his rented room in the lower level of a hillside house in Laurel Canyon. In the dim light of a desk lamp lay a yellow notepad, four words written in green ink across the top -- Rebel Without a Cause. The rest of the page had been terrifyingly empty for the whole day. Director Nicholas Ray called that night and asked, "How's it going?"

"I haven't started yet," Stern replied.

A pained silence, then that hollow, wounded voice: "You'd better start."

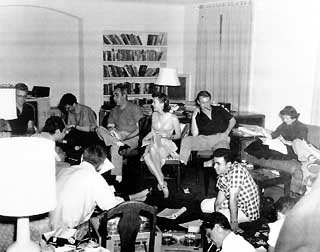

clockwise from bottom left: Nicholas Ray, Stewart Stern, James Dean, unidentified, Jim Backus, Natalie Wood

Guaranteed $1,000 a week and required to meet a 12-week deadline beginning December 30, 1954, Stern haunted the Los Angeles Juvenile Hall to listen to testimony from troubled kids and read case histories until he found his characters.

After Nick Ray's ominous phone call, Stern drove down to Hollywood Boulevard to walk around and think but found himself watching On the Waterfront instead. Overwhelmed by the honesty and courage of the film, he suddenly felt released to write intimately about himself and his friends and their relations with their parents. He sat down and wrote a devastating prologue scene.

Ray was pleased that Stern had finally begun to write and sent him back to Juvenile Hall to study its glass-partitioned offices, which Ray wanted him to use in dramatizing the separation and connection between the principal characters in the opening scene. Completely fired up, Stern was able to write the entire police-station sequence in one day. Three weeks later, he handed Nicholas Ray 42 pages of Rebel.

Satisfied that he had found the right screenwriter, Ray began to cast the picture around the "force that was James Dean." Moving into a Warners office with a desk full of "the detritus of other agonies" and walls of peeling paint, Stern amazed himself by turning in a completed script of 126 pages by February 25. He explains, "I was caught up in the same kind of fervency and speed that the characters were. It was a time in my life when I had so much to unload, so many things to figure out through the writing of that script." After ongoing consultations with Ray, Weisbart, and the cast, Stern produced the final draft of Rebel on March 25, three days before filming began, 12 weeks after Stern was hired.

Stewart decided to go to New York to avoid being on the set. "Jimmy had confided to me his doubts [about Ray], and I knew if I were there, he would be pulling me into his dressing trailer all the time to ask me what I thought. Given Nick's sensitivity and the importance to him of his relationship with Jimmy and how totally that film would depend on the state of the relationships between the director and his actors, I just felt it would be too destructive if I couldn't control myself about things I saw happening that I didn't like. I decided to stay away."

Nicholas Ray finished shooting his version of the picture on May 26, 11 days over schedule, and the next day went "off-salary." The editing of Rebel was supervised by producer David Weisbart, who had been an outstanding editor (A Streetcar Named Desire) before becoming a producer. When Stewart Stern saw the first preview, he considered it endlessly long and overindulgent: "You thought people would never get to the line they were saying. The pauses were all so pregnant, and Nick had stuck in lines I hated and cut out things I loved."

In the theatre lobby, Stern ran into Weisbart and told him,"I hate this film."

David replied, "Well, it's got a ways to go."

The two sat down with Jack Warner and his assistant Steve Trilling and talked for hours about how the next cut could be improved. At the same time, Stern recognized Ray's brilliant contributions -- "the color palette, the ballet of that knife fight, and the whole Götterdämmerung aspect of the chicken run and burning car and more. Much more."

By the time the film was released in late October 1955, James Dean had been dead a month. Stern couldn't watch the film without mourning his lost friend. Once he brought himself to see it years later, he was finally able to tell that it was the picture that moved him just as much as the death of its young star.

Along the paths he now walks through the arboretum near his home in Seattle, Stewart has "animated the trees with the souls of deceased friends" so he will have "a place to put my thanks because all those people changed my life." As he passes by, touching each tree, he greets the "large, beautiful, big-leaf maple covered in moss halfway up the trunk in the deep shade of other trees." In that tree live Jimmy Dean, Natalie Wood, Sal Mineo, David Weisbart, and Nick Ray. Though disappointed that not all the carefully crafted words and relationships made their way from script to screen, Stewart Stern has finally accepted the cinematic version of Rebel Without a Cause and is grateful for its long and meaningful life.Source:

http://www.austinchronicle.com/issues/dispatch./2000-06-16/screens_feature2.html

0 comments:

Post a Comment